by Ethan Shaw

In this final installment of our three-part series, we consider the extirpated Oregon grizzly’s ecological world and briefly look at the status of the existing grizzly populations nearest the Beaver State.

Read Part 1: Oregon as Grizzly Country and Part 2: The Last Grizzlies of Oregon

The Oregon Grizzly at Home

With the extirpation of the grizzly, Oregon lost one of the creatures most capable of (and enthusiastic about) reaping its great and varied bounty—from the bulbs of the alpine meadows to the seafood litter of the strand. Though Euro-American accounts of grizzly habits in Oregon are sparse, we can infer some of the bear’s lifeway here based on what we know from California, the Northern Rockies, the rain-coast of Alaska and B.C., and other better-documented regions.1 2

|

| Black huckleberry in the Strawberry Mountains - a grizzly delicacy. (Sarah West) |

We can imagine the Oregon grizzly tracking vegetative greenup across the springtime lowlands and the summertime mountains; seeking out rank bottomland swales of horsetail, cow-parsnip, angelica, and sedges; chomping through streamside briars of salmonberry and thimbleberry; grazing in glades of bunchgrass, clover, and dandelion; excavating yampah roots and brodiaea bulbs and pocket gophers in valley prairies and on windblown mountainsides; flushing the calves of Roosevelt elk from Coast Range alder groves or stalking rut-addled wapiti bulls in the late-autumn canyons of the Northern Blue Mountains; swatting the salmon out of whitewater rivers; slurping huckleberries prospering in the mid-elevation shrubfields maintained by wildfire or aboriginal burning; clawing open the hives of yellow-jackets and the nests of western thatch ants; raiding the pine-nut caches of nutcrackers and squirrels; munching Garry and black-oak acorns in sunny parkland groves; relishing the manzanita and madrone berries and wild plums of the Klamath chaparral; and routing pumas and wolves off their bighorn, elk, or deer kills. And maybe—like her brethren in California and Alaska—a grizzly snuffling her way down to the Pacific surf might dine on the fetid carcass of a beached whale, harbor seal, or sevengill shark, or a litter of belly-up crabs, or even a heap of bull kelp. (Imagine the giant clawed tracks in the sand, the post-blubber-bonanza naps behind spruce driftwood.)

|

| Roosevelt elk |

Observations from California when that state was grizzly country highlight the importance of acorns in the bears’ diet across much of the state. The mast in the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue valleys and the Klamath foothills must have been a true linchpin of the Oregon grizzly’s seasonal round. Numerous California observers reported grizzlies breaking off low-hanging oak limbs to get at the nuts. And bears could be equally heavy-handed when gorging on wild fruits. A traveler along the Salmon River in the California Klamaths witnessed what grizzlies could do to a big ripe plum thicket: “a scene of devastation and ruin,” the bears having “broken and torn down every tree, smashing and destroying such fruit as they could not eat … ”

The lost Oregon grizzly’s geography is still all around us, and not just in the phenological cycles that once fed the bear and which still ripple across the landscape. We can imagine afternoon grizzly daybeds in dense groves of mountain-mahogany or foothill Douglas-fir; winter dens within black lava caves or amid the roots of hoary old mountain hemlocks or subalpine firs; beaten-down bruin trail networks through Siskiyou chaparral jungle. We can gaze over the verdant cirques of the high Wallowas or the Cascade Crest and see, in the mind’s-eye, the farflung mating grounds of vanished grizzlies. We can lightly touch the bark of centuries-old ponderosa pines, Engelmann spruces, or Pacific madrones, and wonder if a big grizzly ever scratched his mighty back upon it.

Close Quarters

|

| A Yellowstone grizzly (Jim Peaco, NPS) |

Grizzlies shared their highest-quality foodstuffs with indigenous Oregonians. Indians and bears mingled at salmon runs, mast groves, and fruiting thickets. As any hikers who’ve clapped and “Hey, bear!”-ed their way through a doghair wood in Yellowstone or an alder chute in Glacier can appreciate, the prospect of an abrupt, up-close grizzly encounter in heavy cover is mighty unsettling. Imagine entering a wall of thick manzanita, or a half-sun/half-shadow oak copse, or the rainforest briars along roaring rapids, and suddenly coming face-to-face with a griz seeking just the wild delicacies you’re after.

The Nearest Grizzlies

I’ve presented a casual overview of some of what we know about the grizzly’s historical presence in Oregon. The prospects for the bear’s future existence in the state must be addressed elsewhere (you can read one analysis here3), but let’s briefly review the status of the populations nearest the Beaver State.4

|

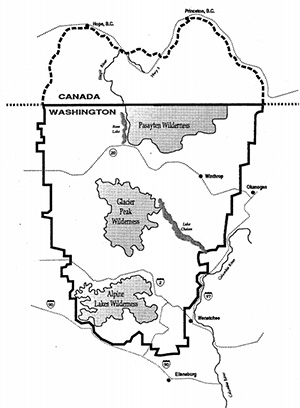

| US Fish and Wildlife North Cascades recovery zone for grizzlies. |

A few dozen grizzlies are thought to roam Washington’s North Cascades, which, as already mentioned, are currently being debated as a site for reintroduction. In 2010, a hiker photographed what biologists confirmed as an adult griz in the upper drainage of the Cascade River; the previous authenticated record from the U.S. portion of the sub-range came in 1996, when a sow and a cub were sighted in the Glacier Peak Wilderness.5

Another official grizzly recovery area that’s been in the news lately is the Bitterroot Mountains (aka Salmon-Selway) zone, widely regarded as some of the best remaining habitat for U.a. horribilis in the conterminous U.S. While no breeding population of grizzlies is known in the region (roughly 100 miles east of Hells Canyon), dispersing bears have been showing up there lately. In 2013, a sow grizzly (“Ethyl”) skirted the northern Bitterroots on her astonishing 2,800-mile ramble around the Idaho Panhandle and northwestern Montana.6 In 2007, a young male griz was shot in the Kelly Creek drainage of the range; DNA analysis showed he hailed from the Selkirk Mountains of northeastern Washington/northwestern Idaho and adjoining B.C., another island of occupied grizzly habitat.7

Greater Hells Canyon, where some of the last known Oregon grizzlies were killed, could conceivably serve as the portal into the Beaver State for bears dispersing from Idaho—just as it did for gray wolves.

***

The long-term survival of the grizzly depends on multiple core populations linked by habitat corridors to ensure genetic diversity and interchange. We can hope for a time when Oregon’s biggest, wildest country again contributes to the silvertip’s genepool; when grizzly mothers again introduce their cubs to the old bear-customs of the Wallowas or the Klamaths: what to eat and when, where and how to dig the winter den, what sort of timber to hole up in when a big boar—or a human being—comes over the rise.

|

| A wolf follows a grizzly bear in Yellowstone National Park. Hells Canyon in NE Oregon could be a gateway for grizzlies to return to Oregon, much as it has been for gray wolves. |

[1] Hamilton, A.N. and F.L. Bunnell. “Foraging Strategies of Coastal Grizzly Bears in the Kimsquit River Valley, British Columbia.” Bears: Their Biology and Management 7 (1987): 187-197.

[2] Mace, Richard D. and Charles J. Jonkel. “Local Food Habits of the Grizzly Bear in Montana.” Bears: Their Biology and Management 6 (1986): 105-110.

[3] Carroll, Carlos, et al. “Is the Return of the Wolf, Wolverine, and Grizzly Bear to Oregon and California Biologically Feasible?” Large Mammal Restoration: Ecological and Sociological Challenges in the 21st Century. Ed. David S. Maehr, Reed F. Noss, and Jeffery L. Larkin. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2001. 25-41.

'

'