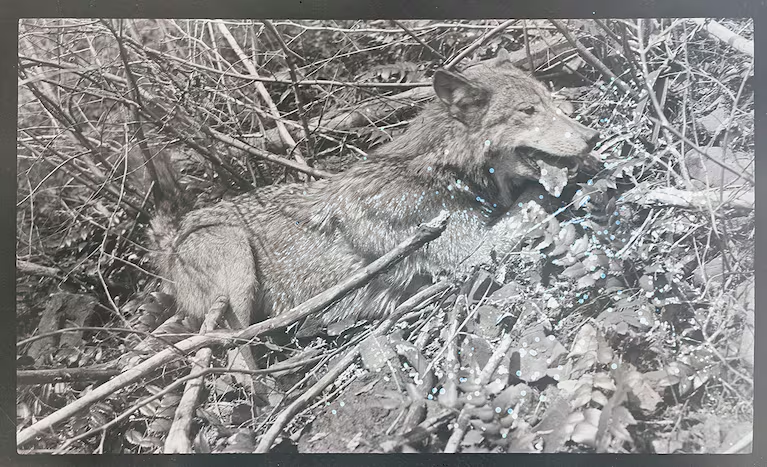

Wolves Come Home to Oregon

After an absence of over half a century, wolves have started making a cautious return in the early 2000s. As of 2022, wildlife officials documented at least 178 confirmed wolves in the state. While this progress is cause for celebration, scientists estimate that, based on available habitat and prey, Oregon could support up to 1,450 wolves. We still have a long ways to go to achieve full statewide recovery.

Oregon Wild advocates for wolf restoration in Oregon by:

- Providing important input and watchdogging implementation of the Oregon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan. This plan guides the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife on all management decisions.

- Stopping harmful state legislation that undermines wolf recovery. Oregon Wild advocates for strong legislation that combats poaching, supports habitat connectivity, and funds critical non-lethal programs.

Support wolf recovery efforts in Oregon!

Send a letter to state and federal managers urging them to support statewide wolf recovery by implementing management practices that prioritize non-lethal measures, reduce conflict, build tolerance, and combat poaching.

-

1947

1947Last recorded wolf bounty paid out in Oregon

In 1843 the first wolf bounty was established and Oregon’s first legislative session was called in part to address the “problem of marauding wolves.” By 1913, people could collect a $5 state bounty and an Oregon State Game Commission bounty of $20.

-

1947-1999

1947-1999Wolves locally extinct in Oregon

-

1999

1999The first wolf in Oregon in nearly 50 years

The wolf B-45, informally called “Freedom” by many conservationists, crossed the Snake River and became the first confirmed live wild wolf in Oregon in about a half a century. She was born to Idaho’s Jureano Mountain Pack in 1997. Although she was soon returned to Idaho, her arrival marked an important first step for wolf recovery in Oregon.

-

2005

2005The first Wolf Conservation and Management Plan

The state of Oregon completed a Wolf Conservation and Management Plan – a way to guide wolf recovery and management in the state. Unfortunately, the Plan was weak, giving ODFW broad authority to kill wolves.

-

2006

2006A flurry of sightings in Northeast Oregon

Several sightings led biologists to believe a number of wild wolves were living in Northeast Oregon near the Wallowa Mountains and the Eagle Cap Wilderness. A wolf found shot to death near La Grande in May 2007 clearly indicated wolves had arrived in the area.

-

2008

2008The first wolf pups born in Oregon

Pups born to a wolf named Sophie (B-300) marked the first wolf pups in nearly 60 years!

-

2011

2011The Journey of OR-7

OR-7 (Journey), a wolf from the Imnaha pack of Northeast Oregon, made international headlines when he crossed into Western Oregon and then California – marking the first wolf in the state in nearly a century! His incredible travels inspired many and became a symbol of hope and rewilding.

-

2011

2011Eastern Oregon wolves lose Endangered Species Act protections

Due to an unprecedented congressional budget rider sponsored by Montana Sen. John Tester, wolves in Eastern Oregon lost their federal protections. Hours later, Oregon used their new authority to kill two wolves and issue dozens of landowner kill permits at the request of the livestock industry. After peaking at 26 confirmed wolves, wolf recovery stalled.

-

2015

2015Wolves lose state protections

With only 78 known adult wolves in the state, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and its Commission decided to prematurely strip wolves of state Endangered Species Act protections despite what peer reviewed, independent scientists recommended.

-

2016

2016HB 4040 passed

Oregon Legislature passed HB 4040, a bill affirming the delisting decision. This unprecedented move was done to block conservation groups’ ability to overturn the decision in the courts.

-

2019

2019Wolf Conservation and Management Plan updated

The update significantly eroded protections for wolves by lowering the threshold for when the state can kill wolves, removing requirements for non lethal conflict deterrence, and opening the door toward public hunting and trapping.

-

2020

2020Wolves lose federal protections

Trump administration removed federal Endangered Species Act protections for most wolves in the nation, including wolves in Western Oregon.

-

2022

2022Federal protections are reinstated

A federal court reinstated federal protections that had been in place for gray wolves. Wolves are relisted as threatened and endangered in all or parts of 44 U.S. states and Mexico.

-

The Future

The FutureFor many, wolves are a symbol of freedom, wilderness, and the American west, and Oregon’s wolf country contains some of the most spectacular landscapes in the world. Science continues to demonstrate the positive impacts of wolves on the landscape and the critical role played by big predators, and interest in their return is fueling tourism in Oregon’s wolf country and elsewhere in the west.

Key Staff

- Danielle MoserWildlife Program Manager