What's at Stake?

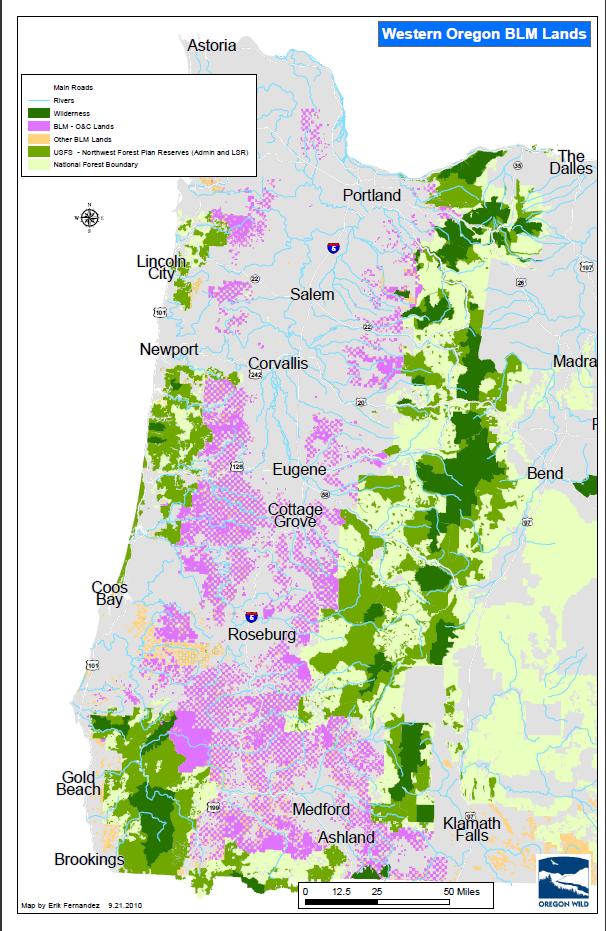

When it comes to the management of public forest lands in our state, most Oregonians think of the U.S. Forest Service. But the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is responsible for more than two and a half million acres of public land in Western Oregon.

While much of this has been heavily logged in the past, nearly one million acres of intact, ancient forests remain on these lands.

The low-elevation forests in the Western Oregon BLM region are critical connecting blocks to the largely mountainous National Forests in Oregon, and are some of the most productive forest regions in the world.

These forests are also extremely diverse, with a variety of species found on the slopes of three distinct mountain ranges: the Siskiyous, the Coast Range, and the Cascades.

The forests feature ancient, coastal hemlock on the Coos Bay District, biologically rich forests on the Medford District, and towering Douglas-fir forests on the Roseburg, Salem, and Eugene BLM Districts. They shelter important salmon streams, provide critical habitat for threatened wildlife, offer incredible recreation opportunities, and provide the scenic backdrop and drinking water for thousands of rural Oregonians. They are our backyard forests!

These forests can also provide jobs and wood products as a by-product of forest restoration, such as thinning young plantations which have grown back after the clearcutting of the past several decades.

History of the O&C Lands

One of the unique features of western Oregon's BLM land is its "checkerboard" pattern in the foothills of the Cascades and Coast Range. Those are the O&C lands (click on map for larger view). These lands were originally granted to the Oregon and California Railroad (O&C), but were re-vested to the federal government when the railroad didn't hold up their end of the bargain, and their management was set forth in the 1937 O&C Act.

When the Northwest Forest Plan was developed in the 1990s to protect fish and wildlife dependent on old-growth forest habitat and healthy streams, these lands were a part of this science-based management plan.

Logging has severely affected much of this land, but the BLM still manages hundreds of thousands of acres of pristine and unspoiled old-growth "heritage forests." Unfortunately, some of the ancient forests that provide critical habitat for threatened fish and wildlife are still being targeted.

Under the second Bush administration, logging interests and the BLM worked together to put these heritage forests on the chopping block. The Bush administration settled a lawsuit brought by the logging industry, and agreed to remove BLM forestlands in western Oregon from the Northwest Forest Plan's old-growth reserve system.

Together, they developed the WOPR (an abbreviation for the Western Oregon Plan Revisions) that would have opened much of the old-growth forests remaining on BLM land to aggressive logging. This plan was found illegal and withdrawn by the Obama administration in 2009. Unfortunately, the BLM is insisting on a new plan that sets a higher timber target. Another new plan (we call it "WOPR Jr.") was finalized in August 2016, and has significant problems. Learn more here.

County Funding and Public Lands

For years, counties with O&C lands received funding based on the amount of timber harvested from these lands. This led to a perverse incentive to log more old-growth forests to pay for basic county services like schools, law enforcement, and libraries. Over time, unsustainable logging practices led to the degradation of fish and wildlife habitat and water quality throughout the region.

Thankfully, widely supported environmental laws were passed in the 1970s to protect clean water, endangered species, and the general health of our nation's environment. The Northwest Forest Plan followed in the early 1990s, and once instituted slowed down the unsustainable and damaging logging of old-growth forests, but also resulted in a decrease in funding for county services.

Recognizing the need for bridge funding to a day when rural economies wouldn't be as reliant upon the boom and bust timber industry, the federal government provided support provided funding for these counties through programs like Payments in Lieu of Taxes and the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self Determination Act (SRS), first passed in 2000. The SRS has since expired, and without re-authorization in Congress county funding is once again linked to logging of public O&C lands.

Today, Western Oregon counties are facing a looming financial crisis due to the end of federal Secure Rural Schools legislation and historically low property taxes. Some groups and politicians have tried to use this crisis to promote a return to old-growth and clearcut logging on federal BLM lands as a means of generating revenue, which would put clean water, salmon, and Oregon's tourism and recreation economy at risk.

t is vital that a reliable, long-term source of funding be found to provide for vital government services, without jeopardizing the conservation of public lands. Instead of attempting to solve the county payments crisis by liquidating public lands through risky logging schemes, a long-term solution to county funding needs to include contributions from federal, state, and county governments.

Conservation groups have proposed a "shared responsibility" plan for keeping county governments in business while not sacrificing clean drinking water, salmon and wildlife habitat, and quality of life for Oregonians. This report is just the starting point for ideas that could contribute to a more sustainable future for Oregon's counties. Ideas include:

-

Transferring most of the 2.6 million acres of BLM forest lands in western Oregon to the U.S. Forest Service could result in tens of millions of dollars in administrative savings and efficiencies, while better managing these lands as a whole landscape for conservation and restoration.

-

Record numbers of raw logs are being exported to China, enriching logging corporations while they pay incredibly low taxes. Reform of the very low state timber excise tax would make these corporations pay their fair share to help struggling local governments and communities.

-

Tax reform at the county level, where we see some of the lowest property taxes in the nation, could help generate revenue.